Custom Search

|

| boat plans |

| canoe/kayak |

| electrical |

| epoxy/supplies |

| fasteners |

| gear |

| gift certificates |

| hardware |

| hatches/deckplates |

| paint/varnish |

| rope/line |

| rowing/sculling |

| sailmaking |

| sails |

| tools |

| join |

| home |

| indexes |

| classifieds |

| calendar |

| archives |

| about |

| links |

| Join Duckworks Get free newsletter CLICK HERE |

|

|

| Slo Mo Shun IV |

by Mike John - Logan City, Queensland - Australia |

In November 1949, there was a newspaper story in the far away Australian Cairns Post announcing that a boat was being prepared in Washington, USA for a shot at the World’s speed boat record. How did a faraway Australian reporter, in what then was a very small town on the far north coast of Queensland, happen to note a boat on the other side of the world? Queensland did not have a computer until 1962 (which was at the University of Queensland and cost £135,000 and was the size of two houses) so there was definitely no Internet back then. As it turns out, in the boating world this boat was more famous than Laurence Olivier who won the Academy Award for Hamlet in 1949. The reporter wrote: ‘A boat that outruns aeroplanes on Lake Washington is being groomed for an assault on Sir Malcolm Campbell's world record of 141.74 miles an hour’ (Cairns Post, Tuesday 29 November 1949, page 4). The owner, Sayres, was tight-lipped on the boat’s chances of breaking the record. The hydroplane involved named Slo-Mo-Shun IV, a type of boat that is now considered by many as just plain dangerous (they flipped like in this video which happened just days ago), broke records and won races. Sayres was not sure of his success as he told the reporter: ‘Whatever you write, underline the ‘if’. Ted Jones, a boat designer working as a supervisor at the Boeing Aeroplane Company plant, apparently designed the boat. Allegedly, as the builder Anchor Jensen may have had more to do with the design than published, but this was never confirmed. The allegation is that Jones was slow with plans and Jensen had to do much of the designing himself (David D. Williams, Hydroplane Racing in Seattle, 2006, p. 29). Nevertheless, ‘The challenge was to design a hull that can take full advantage of the power plant’, Sayres said. The reporter’s notes on the mechanics of the boat spark interest. He wrote:

Sayres claimed he named the boat in a kidding moment. We need to travel in time before and after this clipping to see how it faired. The end of the story is clear. Although the boat was damaged during an event, one of the 4,500 pound Slo-Mo-Shun IV’s runs was quite recently. On the back of a truck she was moved to the Museum of History and Industry's new home at the Naval Reserve Building (Armory) at Lake Union Park in Seattle on Tuesday, April 3, 2012. The move notice gave more of a clue to her success. ‘Slo-Mo-Shun IV is an all wood and metal boat that set a world's speed record of more than 160 MPH on Lake Washington and in 1951 won the Gold Cup Race’ (seattletimes.com). That is 257 kph for the metrically inclined.

There are a couple of videos: One and Two. Before the first record was set, Sayres it seems had always enjoyed speed and he had a long held desire to drive a boat faster than anyone had done before. At some time prior to 1948, Sayres bought a used boat that had at one point done 80mph and named it Slo Mo Shun. Later he built Slo Mo Shun II and Slo Mo Shun III. He watched the Gold Cup of 1948 and realised hydroplanes could be improved. This was the motive for Slo Mo Shun IV. Sayres considered building racing boats for a living and he partly developed Slo Mo Shun IV as a step for entering the market. It was launched in October 1949. In February 1951 Slo Mo Shun V was commenced and it was finished in July 1951. Sayres did not drive the enclosed course races. Sayres spent about $100,000 building and developing the Slo Mo Shuns. Sayres attempted to claim deductions for the building and running of his boats as a business but it was ruled as a hobby and his claims were refused (Reports of the Tax Court of the United States. v. 28 1957 Apr-Sep). The designs of the two sister boats were purposefully different. Slo Mo Shun V, the sister boat, was able to make tighter turns at higher speeds. Slo Mo Shun IV was created for speed in straight runs. However, Sayres found complications with the higher speeds in both boats, especially sheering propellers and bending rudders. The propeller shaft was replaced with a high strength monel shaft which basically allowed the boat to keep racing. It was that critical. The rudder was offset from the propeller by seven inches to starboard, the rudder was made from cold rolled steel and the rudder shafts and posts were also monel (MotorBoating, Sep 1952, p. 15).

Some hydroplanes of the era flipped the bow up and somersaulted backwards. This problem was avoided in Slo- Mo-Shun IV by providing an inverted pyramidal step under the bow, to serve as a fourth point of suspension. It acted partly like an air spoiler in the tunnel between the two sponsons. The resulting drag held down the bow and there was no tendency for the boat to do a backward somersault. In rough water, the pyramidal bow plane spreads the water surface so that the boat is safe at speeds at which the ordinary hydroplane would run wild or pound itself to pieces.

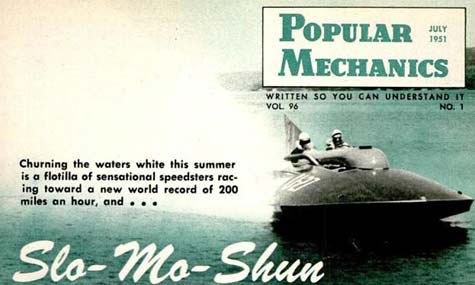

Source: Popular Mechanics, July 1951, p. 69. Slo-Mo-Shun IV rode high and only one of the blades of its two-bladed propeller was in the water at a time. The propeller was turning at about 10,000 revolutions per minute. The step-up gearbox was bolted directly to the rear of the engine, permitting the use of a short, straight, drive shaft instead of the customary transfer drive from the bow. The boat was 28.5 feet long and had a beam of 11 feet 5 inches. The air fin at the rear was simply a stabilizer and wasn’t used for steering (Popular Mechanics Jul 1951, p 67). Finally, a fine video of both Slo Mo Shun’s racing is on seattlechannel.org (it takes a minute for this video to load.) Mike John, your faithful Duckworks editor. If folks are interested I have started a facebook group on Woooden Geared Clocks. I find them fascinating. |

To comment on Duckworks articles, please visit one of the following:

|

|